This weekend, hundreds of people from dozens of countries will gather in Singapore to discuss the future of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a multinational organization that oversees the address book of the internet thanks to a contract issued by the U.S. government.

The contract expires in September 2015 and the U.S. Commerce Department announced last Friday that it would eventually transfer key internet “domain name functions to a global multi-stakeholder community.” Some Americans worry this will cede “control” of the internet to nations that will impose regulations that change the basic open character of the internet and make it less hospitable to American interests.

It is important to remember that no one, no government and no organization “controls the internet.” ICANN is a crucial cog in the functioning of the internet because computers (and the people who use them) cannot find each other on the internet without Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. ICANN oversees how those addresses are doled out and how they are named. No IP address; no connectivity between your computer, smartphone, or tablet and others. No IP address; no website.

It is such a huge system that the original creators of the internet in the 1970s-1980s substantially underestimated how many addresses would be needed. They built a system that allowed for about 4.3 billion addresses, and the world has been scrambling in recent years to expand to a system, called Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6), that allows for roughly 340,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 addresses. (Yes, that’s right.)

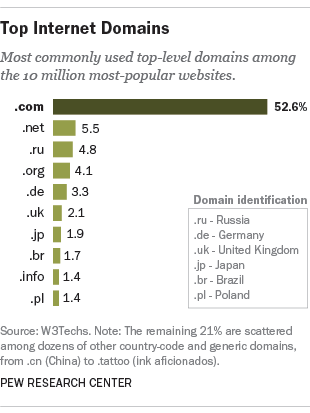

ICANN’s big job is to ensure that when users try to access a website or send an email, they end up in the right place. It is perhaps best known for coordinating the Domain Naming System (DNS), the key bits of information that fall on either side of the “dot” in a web address. It set up the nomenclature for the right side of “top level domain,” which, for most of the history of the Web consisted of a few familiar suffixes – .com, .org, .net, .edu, .gov, .mil and some country-specific domains like .af for Afghanistan and .by for Belarus. A raft of new top-level domains are now being reviewed or have recently been approved, many of which are trying to tie a top-level domain to a particular topic such as .museum or .plumbing.

ICANN makes arrangements with “registries” to administer those top level domains. In turn, those accredited registries handle the material on the left side of the dot – selling or providing local domain names to websites or email providers.

The internet would break down without this kind of basic coordination, but there are plenty of important things on the internet that ICANN does not regulate:

- Bad actors on the internet: ICANN is not a policing enterprise. It does not investigate hackers or spammers or those accused of trademark violations (e.g. an organization pretending to be a famous brand product).

- Content on the internet: ICANN is not in the business of monitoring and regulating child pornography, hate speech, scams, spoofs or other illegal material. Laws in international organizations, or in countries, states or localities, govern such activity, and the law enforcement personnel in those realms are responsible for those policing functions.

- Internet access itself: That is provided by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) that are not under the control of ICANN.

Still, there are really crucial internet “real estate” issues for ICANN to sort out and any number of legal issues that bring it into court.

Even more important, at times, are the political atmospherics of ICANN. Despite the fact that most ICANN board members are not American, despite the fact that the CEO is Egyptian, there are many in the international community who assume that the U.S. has outsized influence on the group. In the wake of revelations that the National Security Agency has been gathering up enormous amounts of information on people’s internet activities, several countries have announced plans to host meetings on the future of internet governance that will push for non-U.S. control. Some believe that the U.S. announcement was aimed at reassuring other nations that it would not retain control of ICANN.

As the Singapore meeting proceeds it will be interesting to see if the U.S. provides more details about what kind of “multi-taskholder” structure would be satisfactory as a body to run the organization. The Commerce Department statement only specified what it would not be: The department “will not accept a proposal that replaces the NTIA role with a government-led or an inter-governmental organization solution.”

Obama Administration officials emphasized that this transfer was not handing power over to Russia and China or other governments with histories of censorship. Perhaps they were aware of the broad international sentiment against internet censorship that the Pew Research Center just reported.

There are important questions to resolve in Singapore and beyond: how the board and staffing of ICANN will be structured, who gets to pick people for which jobs, who gets to vote when policy is made, how non-government stakeholders like companies and non-profit organizations will have a say in ICANN affairs, and what kinds of appeals mechanisms will be available to those who are on the losing side in policy choices.

It would not surprise many if the transfer of ICANN to another overseer extended beyond the September 2015 end of the current contract – perhaps well beyond.